Whilst we live in a world where we are bombarded with information and it may seem like we have the world at our fingertips, we only discover as much as we are allowed to. There is much that is concealed and lost. As ordinary citizens, we look towards institutions of education to support us through this journey. Museums and galleries are beacons of information, curating work to help us wrap our minds around what goes on in the world. The colonial period stole so much from others only to then be buried in white shame and fear, yet now decolonisation efforts prove to push this into the forefront. With the exhibiting of El Anatsui’s five decades of work at Talbot Rice Art Gallery, we can explore how ordinary citizens rediscover and retrieve what has been erased during the colonial period.

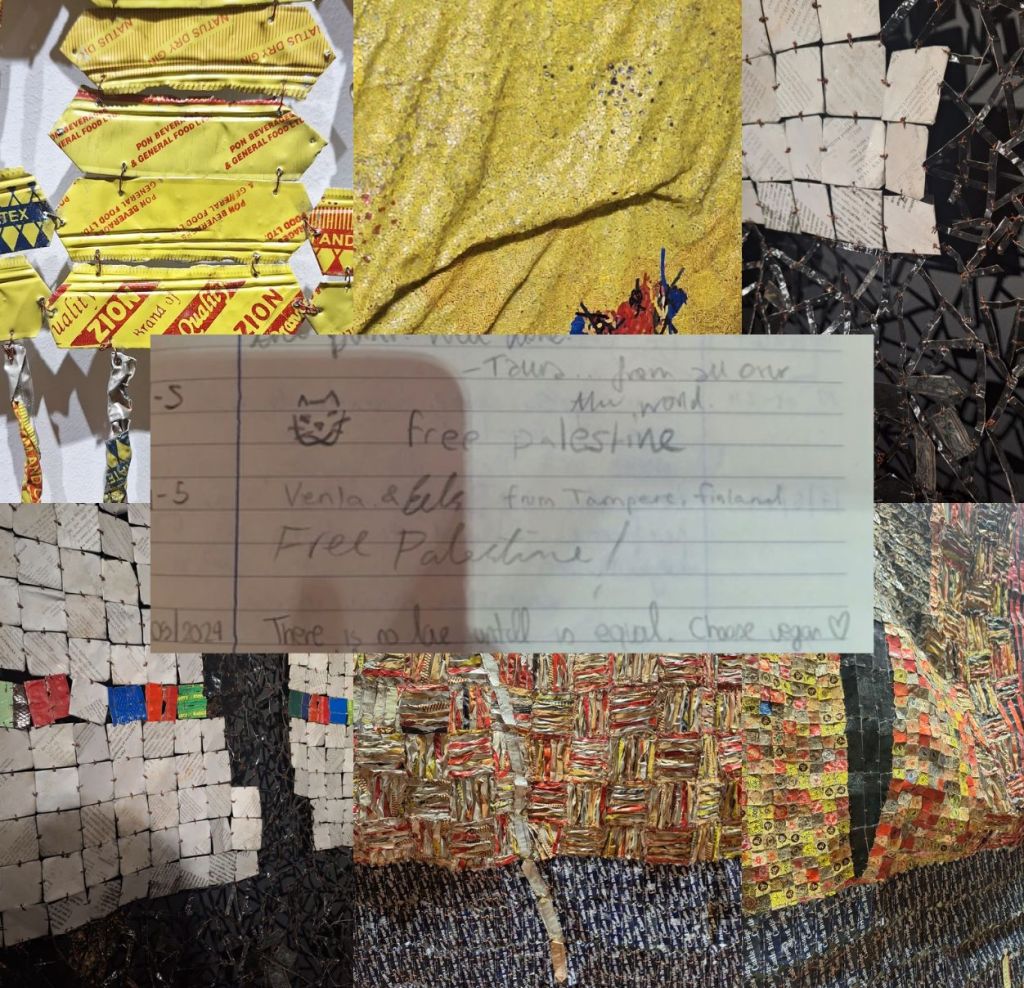

Upon entering the exhibition, I was blinded by a yellow tsunami of light. Covering every inch of the huge white wall was the weaving together of hundreds aluminium bottle tops, moulded to create these beautiful heavy forms whilst playing with colours reminiscent of youth. It felt all consuming. The closer you got, the more you felt that it would simply swallow you whole. Yet it took facing the artwork head on to appreciate the materials more fully. Something you would normally throw away without giving a second thought had now become the focus of the room. With artworks produced with waste material from bottling and print industries in Ghana and Nigeria, he uses traditional techniques to reflect on the post-colonial legacies in society. Yet when I looked around the room, what was evermore engulfing than the art was the building itself. Walking through the doorways only to be confronted by the (literal) grand pillars of colonialism.

The exhibition itself is curated like an ethnography, a tool to tell a story that reflects upon wider ideas of the world. As anthropology “imagines itself to be the voice”, there must be an awareness of representation when doing this (Simpson, 2014). With the name ‘Scottish Mission Book Depot Keta’ taken from El Anatsui’s upbringing, where a Scottish missionary groups provided him with books and materials to begin his experimentation with art. Immediately, we connect Scotland’s colonial legacy in Ghana, showing the reason of importance for this exhibition. The University of Edinburgh’s wider links to colonialism as an institution makes this an increasingly monumental symbol. With the Talbot Rice Gallery being the university’s former natural history museum, the ghost of colonial ecological trophy displays haunt the curatorial halls. As it being such a large educational institution, The University of Edinburgh is looked upon being a space to disperse thought, as so, it pushes colonialism legacy into the forefront by allowing it the spotlight it deserves and the visibility to large audiences. Ordinary citizens are able to walk into this space and either receive exposure to a part of their history that is silence or receive the representation they deserve. Yet is this as true as the University would like it to appear as? Zoe Todd (2016) writes as an indigenous feminist her response to a lecture she attended by Bruno Latour at the University of Edinburgh. The ideas he presents echoes of indigenous scholarship, but his citations are the same white men anthropology was built on. Todd looks towards Ahmed (2014) to describe these institutions of ‘white men’. What she says is that “whiteness is a lightening of the load”, as concepts of indigenity and POC are deemed to much until there is a white intermediary to make it acceptable. El Anatsui himself credits the Scottish Missionaries fromthe start of the exhibition, showing that he too is aware of the fact that he must cite a white man to be able to get this position in art/academia (Sara Ahmed, 2014).

Whilst I was unable to physically engage with other visitors, I was able to still interact with them in other ways. Leaning over my shoulder, I watched two older English women say how beautiful the ‘Women’s Cloth’ work was. They neared to see the materials more closely, before pulling their hands out of their pockets and pressing their fingers along the bottle caps. Clearly impressed by the aesthetics of the work, they promptly walked past the descriptions to ‘ooh’ and ‘ahh’ at the rest of the buildings and its contents. Yet this didn’t feel like a substantial enough way to understand how citizens could rediscover and retrieve anything from the exhibition. Yet I followed behind them, doing four or five laps of the gallery to make sure I wasn’t missing anything.

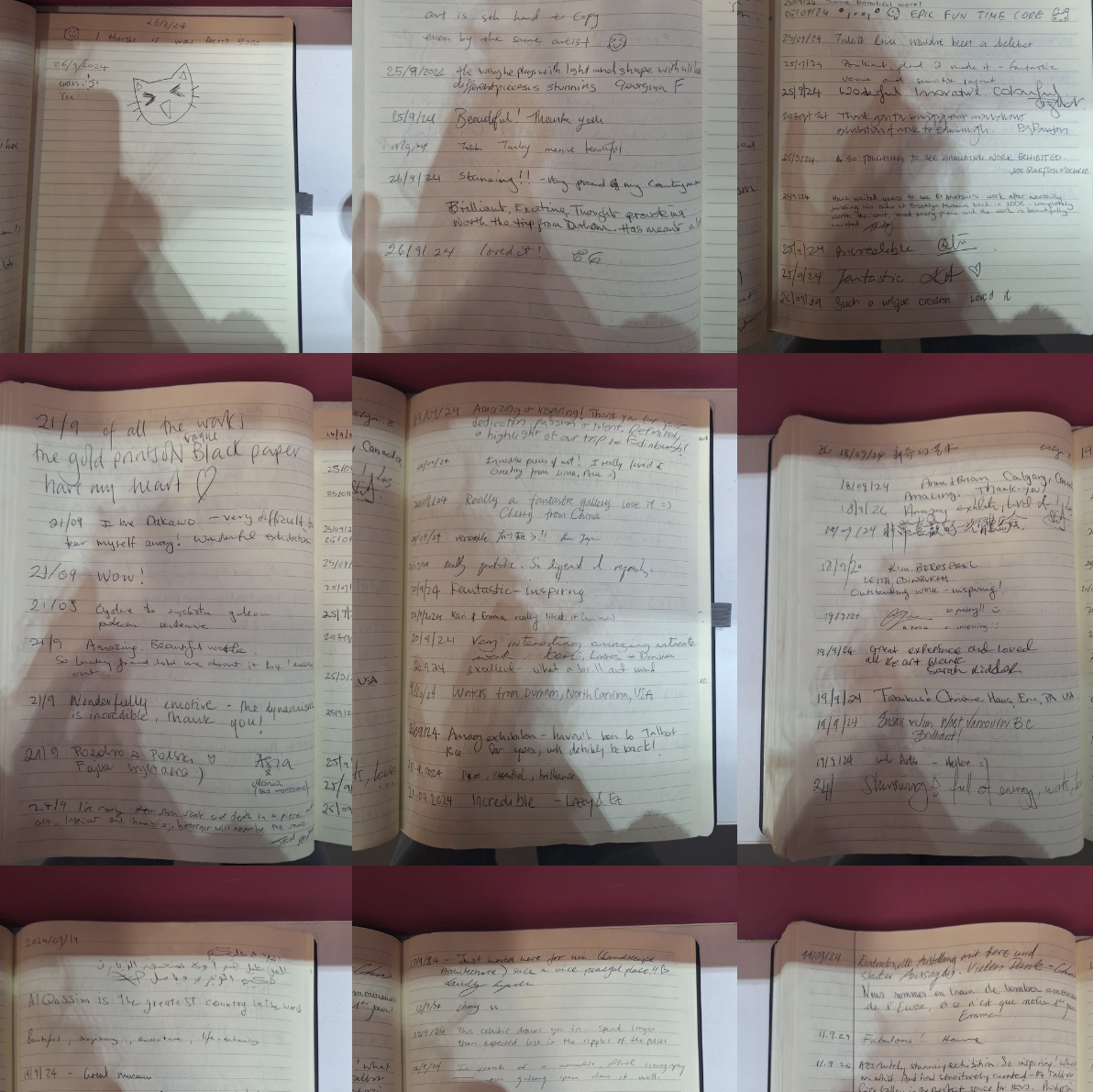

When I finished circulating the building, I returned to the reception space and turned over the pages of the visitor book. Curious to see what commentary it had prompted out of people, it gave me a glimpse into what Talbot Rice had managed to infiltrate people’s minds with. There was plenty of commentary on the visuals of it all, naturally because it is an art gallery. Tracing the writings saying “stunning”, “this place is very inspiring”, “I love coming to Talbot Rice – and this exhibition is why!”, “the work and the show is so beautiful”. Lots of high praise that seemed to stem from the beauty of the exhibition and the impact of the curation within the space. Yet what I also found were people who were uncovering ideas they hadn’t heard of before, “at first glance I didn’t know what it meant, but the more I looked, the more I saw beauty and effort in each piece”. Another comment made me realise how audiences were not just uncovering colonial histories but also rejecting the colonial present through comments like “FREE PALESTINE”.

Whilst seeing “FREE PALESTINE” written in the visitor book shows that visitors were engaging with the themes, the leather bound “University of Edinburgh” book seemed like it might spontaneously combust with irony. Our University has repeatedly taken down the memorial dedicated to the martyrs of Gaza that sits in the quad where Talbot Rice is. At some points, El Anatsui’s artwork was hung outside over the very same spot the memorial stood. A university spokesperson described the memorial as “threatening”, which poses the question of why El Anatsui’s colonial testimony is less ‘threatening’ than the one of Gaza. Zoe Todd references Bauman (1989) when he speaks of the Holocaust saying that “humanity is responsible and humanity must be willing to face itself and to acknowledge its role in these horrors… we must do so in order to ensure we never tread the path of such destruction again”. Stemming from the idea that genocides caused by white supremacy are treated like unfortunate singular events, Bauman is saying that we need to confront the reality that this was purposeful and will happen again. Decolonisation is therefore not the confrontation of singular horrific actions but rather the confrontation that the entire system is built off these concepts. Therefore, if the University of Edinburgh allows El Anatsui to present his decolonisation work to citizens but not grassroots activists and students, ordinary citizens are not allowed to retrieve and rediscover colonial legacies without being guided by the very creator of them. If the places that disperse education and are leading decolonisation theory are the ones who are choosing to reproduce white supremacy, then there will be no shifts in true understanding (Todd, 2016).This is not to dismiss the decolonisation efforts in which individuals at institutions make or the effort and hard work of everyone at the exhibition, rather it is the opposite. We must push for a collective realisation of what is wrong by refusing to engage with the system of white supremacy. If this exhibition planted the seed for you to understand anything, one would hope that it is to not trust the systems of thought that are in place. The question is framed as how citizens engage with what has been erased in the ‘colonial period’; implying that it is something that lies in the past, when in reality colonialism is an ongoing state and we are watching history be erased in real time. So if citizens are to rediscover anything, it is the fact that colonisation is alive and thriving. It festers under the floorboards of our institutions, as we stand and observe the paintings that eventually chip away to mean nothing. To combat this we must call for a “permanent decolonisation of thought” (Viveiros, 2009) by refusing to acknowledge the white man institution to prove what we are saying is valid (Sara Ahmed, 2014). Erect your moments and cite your indigenous scholars, then we can reimagine history and the future together.

Bauman, Z. (1989). Modernity and the Holocaust. Contemporary Sociology, 20(2), p.216.

doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2072918.

Sara Ahmed (2014). White Men. [online] feministkilljoys. Available at:

https://feministkilljoys.com/2014/11/04/white-men/.

Simpson, A. (2014). Mohawk Interruptus Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States.

Duke University Press.

Todd, Z. (2016). An Indigenous Feminist’s Take On The Ontological Turn: ‘Ontology’ Is Just

Another Word For Colonialism. Journal of Historical Sociology, 29(1), pp.4–22.

Viveiros, E. (2009). Cannibal Metaphysics.