Latin American music has asserted itself into the mainstream, with its heavy dembow beats and accents that the ‘Real Academia’ would turn their nose at. Labelled as ‘ignorant’ music, the journey for reggaeton to hit radio stations has been a struggle for racialised bodies to make themselves visible. Though the ‘objects’ I have chosen are frequently looked as being ‘non-intellectual’, I see them as being equally as worthy as any other source – historical sources and academia are often perceived as being “springs of real meaning”, when in reality they are representative of “fonts” of colonial truths (Dening, 1995). Here we can see how the enslaved ‘other’ went from being a savage to slowly being interpreted as being a ‘barbarian’ (Trouillot, 2003). With the original ‘discovery’ of the ‘other’ generating the idea of the ‘noble savage’ (a romanticised idea of these communities), at some point the ‘noble’ aspect seemed to fade and only left the ‘savage’ aspect. The ‘savage other’ was assumed to be non-threatening, passively allowing the colonialists to exploit and examine them. As colonialism intensified and the ‘other’ resisted/threatened this new order, this was when perceptions shifted from ‘savage’ to ‘barbarian’ – as they realised that ‘other’ was capable of resisting. Combining that with the context of this essay is for us to understand how the music of working-class and racialised communities has manifested itself in the context of a modern-capitalist world (Rivera, 2016). This piece of work will focus on deconstructing music’s role in the resistance against racialised realities in Puerto Rico; examined through Ledru’s map of Puerto Rico, an ‘underground’ mixtape, and a video from the ‘Ricky Renuncia’ protests.

ANDRE PIERRE LEDRU – MAP OF PUERTO RICO

The first written record bomba was by botanist and geographer Andre Pierre Ledru. When he was working on cartographic surveys of Puerto Rico, he witnessed and wrote about the dances and songs he witnessed on the sugar plantations. Although Ledru’s maps are the official result from his trip, his research from this trip outlining bomba is what he is remembered by. The object is not representative of bomba, but rather more reflective of the spatial and oral survival of black history at this time. With nobody to keep a physical record of black histories, its survival is based on the environment itself. There is no physicality to this music, it relies on the improvisation of movement and rhythm – but its legacy is strong to this day on the streets of PR. Bomba is specifically important to Puerto Rican heritage because it emerged from the sugar plantations as a way for enslaved people to communicate discreetly. During the bailes de bomba slaves planned their escapes which led to a suppression of these musical manifestations. Whilst they could stop them from coming together, they couldn’t stop the people from using bomba to preserve their African heritage and communicate with each other. Bomba has faced scrutiny as the nature of the genre is that you only require a dancer, a singer, and a drummer. As the enslaved African people came from many different areas, nobody spoke one singular language. This is how bomba ended up relying on the lyricism of body language. Yet from the plantation owner’s perspective, this was an “expression of primitive frenzy [where] the dancers gesticulate and scream songs of naive contents” with “grotesque rhythms”.

In the map created by Ledru, we can discover the geographies of slavery to realise that the history of black diaspora is practiced in its spatialised acts of survival (McKittrick, 2013). Bomba was created through the plantation lives, but it was exercised outside this space as a “provided a rare setting in which the enslaved could assert their humanity and respect their own culture”, therefore intertwining bomba in the urban environment and with blackness. And yet this could only have ever occurred in the context of the plantation system and in the aftermath of transatlantic slavery (Gemmett, 1970) – it is a mode of survival that emerged within the “time, space, and terror” of the plantation (Woods,1998). A violence for the sake of the colonial economy, but encouraged by the idea that black people were animals – unable to consent or feel pain. The terrors of life on the plantation were ones of physical sufferings and rape but also a stripping of identity and depersonalisation, this is the “brutal exercise of power that gave form to resistance” (Hartman, 1997). In the aftermath of slavery, black history can sometimes feel defined by the plantation setting entirely; using this “common memory image” (Keeling, 2007) to reinforce that to be black is to be silent, suffered and abused. Bomba’s very existence disregards that fact though, formed on the outskirts of the plantation to show that the racialised and abused members of society would find a way to create a new cultural identity from these inhumane circumstances. Enslaved people found a new way to reclaim their bodies and consent through the collective improvisation of music. Though Puerto Rico’s racialised resistance is not written down in history, it exists through invisible networks of resistance. Bomba has remained socially relevant, becoming a part of Puerto Rico’s rich cultural tapestry. Despite the best efforts of colonial powers to suppress bomba, it was kept alive throughout the centuries by the afro latino communities who continued to convene on the streets for the ‘bailes de bomba’. Its contributions to the wider latin american community have not gone unnoticed, as it paved the way for the entire ‘underground’ movement that developed into reggaeton.

‘UNDERGROUND’ MIXTAPE – PLAYERO 36

Without bomba, the ‘underground’ mixtape could never exist. The origins of the music genre ‘reggaeton’ are rooted in dancehall, hip-hop, and bomba. In the 1990s, though, it had not been given that genre label and was simply called ‘underground’. It was music that reflected the lifestyle of the ‘barrio’ [neighbourhood]; although some of the lyrics were explicit in sex, drugs, and violence, it was still a reflection of the lived experiences for many. Underground was blamed for the criminal activity in Puerto Rico, when in reality the crime that has permeated from the structural conditions of a colonial government. If a ‘narco-culture’ or violent narrative was employed in ‘underground’, it was a result of the underdevelopment occurring in the ‘barriadas’ [slums] and ‘caserios’ [public housing projects] – a space primarily housed by Afro-latinos. However, ‘underground’ emerged from these conditions and the movement of other black music movements at the time. These living conditions were entrenched in rising rates of crime and violence, inherently leading to this style of music to become synonymous with drug syndicates. In 1993, the new crime fighting legislation “Mano Dura Contra el Crimen” [Iron Fist Against Crime] consisted of increased policing in public spaces, which then mostly concentrated in the slums and projects (LeBrón, 2018). The perceived relationship of underground with crime meant that government bodies needed to end this music that enabled criminal and immoral behaviour (Rivera-Rideau, 2015). In February 1995, the Drugs and Vice Control Bureau of the Police Department of Puerto Rico considered the threat of ‘underground’ to be pressing enough to raid six record shops located in San Juan. However, it went beyond just the record stores. Police began raiding public schools, monitoring low income neighbourhoods and LGBTQ+ clubs, leading to the hypervigilance of non-white people’s sexualities in Puerto Rico by enforcing the white socially acceptable sexual etiquette (Lebrón, 2021). Despite these best efforts, they could not suppress ‘underground’ entirely, with the musicians and listeners burning the music onto CDs and playing the music secretly.

The rhythmic influence bomba had on underground is obvious in its sound, but the culture of resisting a colonial state remains at its core. Underground was seen as dangerous not because music evokes moral panic, but rather because it had the capacity to push back against the dominating narratives of race that thrived in Puerto Rico. Black identity was being centered within Puerto Rican identity and underground was highlighting the disparities of justice that came from this (Rivera-Rideau, 2015). Circling back to McKittrick and the geographies of slavery (McKittrick, 2013); the physical destruction of underground was not sufficient to eradicate it, but rather entrenched it further into black diasporic memory by turning it into a spatialised act of survival against the police state. Like how bomba disrupted the narrative of what enslaved people should be like, underground was similar in how it forced visibility on these oppressed neighbourhoods. The hyper-policing that came from mano dura was another way to dispossess and interrogate these communities to create a militarised anxiety and fear. A lack of change in Puerto Rico’s colonial and white supremacist status replicates the survival methods that were seen on the plantation (Woods, 1998).

‘RICKY RENUNCIA’ PROTESTS

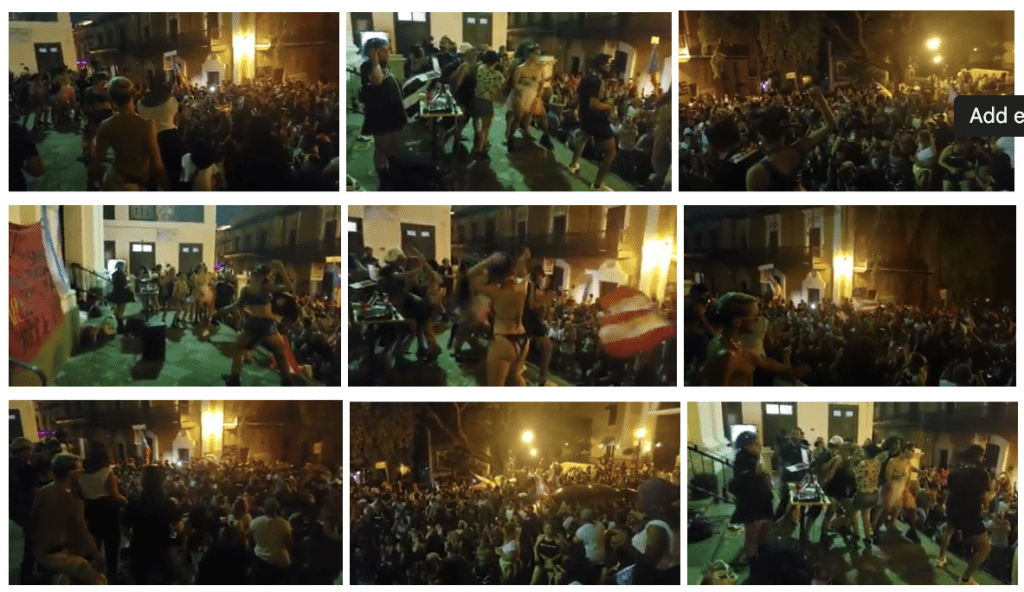

Huge protests erupted in Puerto Rico which called for the resignation of Gov. Ricardo Rosselló. Sparked by the ‘RickyLeaks’ of Telegram chats which exposed the Governor and his peers mocking the casualties of Hurricane Maria, using homophobic and sexist language – as well as the timing of these texts being exposed only days after two officials from Rosselló’s government being arrested for corruption (funneling money into their private businesses). The vulgarity of the messages reached the extent of mocking the dead bodies from Hurricane Maria, “Don’t we have some cadavers to feed our crows [administration critics]?”; these messages were the breaking point for the Puerto Rican people who had their medical resources and aids squandered by politicians, and on top of that had to watch them mock their suffering. This prompted the ‘Perreo Combativo’ movement in response, where they would go outside the governor’s mansion and do ‘Perreo En La Fortaleza’. What ‘perreo’ literally translates to is ‘doggy-style’, but it is a form of dancing which is derived from African dance tradition and is most comparable to what would be colloquially be called ‘twerking’. Like Bomba, this style of dance came from enslaved Africans who were forced to Puerto Rico. Yet, what deviated ‘perreo’ from the traditional influence was the European impact which forced heterosexual pairings onto the dancing (as per western standards). Those from outside the culture also found the dance because of its simulation of sexual acts. From these origins, ‘perreo’ became infected with misogyny and homophobia – once again referencing the moral policing which was observed in the previous objects.

Thinking back to the history of bomba and underground, perreo’s origins are firm in the plantation. The dance is placed in black female flesh and sexuality, which inherently is connected to the plantation bodies where the black female was decided to be overtly sexual to an animalistic extent. Many women and girls were stripped from their ability to consent due to this, subjected to frequent raping and experimentation for gynaecological practice. Part of the terror endured by enslaved people was the “violation of captive flesh”, exemplified in the causation and subsequent treating of VVF (Snorton, 2017). J. Marion Sims used black women in the plantation to experiment on developing new surgical techniques for this disease. These women were placed in conditions where they were at greater risk of contracting VVF because of the plantation setting, making it possible for the disease to not be a causation of slavery but rather a necessary act for it to work. The lack of consent and ‘savagery’ narrative made it so that this medical violence was not something imposed on black women, but rather something that solidified their social position in the colonial hierarchy. Returning to Sadiya Hartman (1997), this social identifier gave way for an “erasure or disavowal of sexual violence [that] engendered black femaleness as a condition of unredressed injury”. Connecting these ideas more closely to perreo, other concepts of the colonial period focused on the size of black women’s buttocks (as it was seen as being bigger than those of white women) to demonstrate that they had smaller pelvic sizes, further showing them to be physically inferior. All these ‘scientific’ conclusions go beyond the conclusion of black people being savages, but specifically target the black woman to be immoral and a fountain of sexual misconduct (Lee, 2014). So to do a dance which draws attention to their ‘physically inferior’ and promiscuous body is a direct act of resistance against the structures that held these concepts in place.

The idea of immorality and sexual misconduct is the main critique of this dance. Even when people of other races and genders take part in dancing to reggaeton, these ideas transfer to them. As perreo is derived from African dances, there is a direct link to the dance being associated with black identity. It is heavily scrutinized because of these origins though, and even more so on its association with the poorer, working classes and frequently judged as being a ‘ratchet’ and ‘ghetto’ style of dance. In Iris Marion Young’s (2005) essays (“Throwing Like a Girl”), she talks about how specific body movements characterise the space which is occupied. In her example, it’s about how a girl throws a ball and how the movements “by projecting an aim toward which it moves, the body brings unity to and unites itself with its surroundings”. Yet to throw like a girl means to throw in a limited manner, in an almost repressed way that is extremely non-fluid and in discontinuous unity with the surroundings. Girls do not move in this way because of how they were brought into this world but rather how the world has projected a social idea on how they can move in the world around them. This demonstrates that one’s body movements can invade a space with a certain social standing. If a boy can ‘throw like a girl’, could we then see how anyone could ‘perrear’ like how the people from the ‘barrios’ would. It shows that for people to congregate in protest against a government that watched the poorest neighbourhood suffer during natural disaster and do a dance that changes the space around them to transform the space into black culture has meaning. If we think about Woods’ (1998) argument about “time, space, and terror”, resistance to racialised realities is directly linked to movement and body. As demonstrated in the ‘Ricky Renuncia’ protests, perreo and reggaeton has been reappropriated as a vessel for a new demographic of misrepresented people. It has become a vessel for LGBTQ+, women, and left wing groups to express their resistance. Through this, there is a strength in reclaiming the dance as a way to come together and fight against the institutional injustices. We can interpret perreo as a radical act of refusal, subverting the colonial gaze by not allowing their bodies to be read through these imposed meanings and reclaiming the body as one’s own. By taking body and movement to the streets, perreo can twist the colonial, white supremacist gaze to see an act of autonomy, pleasure and protest. With the slogan “sin perreo no hay revolución” [“without doggystyle there is no revolution”], we see that perreo and reggaeton is more than just congregation and enjoyment but rather a way of collectivism. Ultimately, what is more obscene: the dancers or the corrupt politicians who mock the dead?

Music and dance does not just interpret the world around us, but it embodies what we are living – the intangibility of this cultural output makes it more powerful than the institutions that try to suppress it (Rodríguez Centeno, 2021). To fight reggaeton goes beyond the genre, it demonstrates a society that has pushed the image of white, ‘decent’, upper class Boricuas (Rivera Diaz, 2024). Bomba, underground and reggaeton pioneers were all disregarded as producers of culture, but even more so as political agents. The music coming out of these spaces makes up more than just popular culture, they are windows into the social, political and cultural dynamics of their geographies and times. Academia and the wider world should look towards these forms of music as a new way to gain access to other people’s lives (Beer, 2012). To conclude my ‘musical’ museum, I believe that the journey through these objects shows how no matter how many narratives are projected onto people in this world, people’s capacities for resistance will always be so much stronger. Though black people in Puerto Rico continually face racialised prejudices, though Puerto Rico remains victim to colonialism; we cannot discredit the efforts made by white supremacist institutions. They shake off the label that they are ‘savage’ or ‘barbarians’. Puerto Rico will keep singing and dancing as long as Boricuas live on the island.

Beer, D. (2012). Hip-Hop as Urban and Regional Research: Encountering an Insider’s Ethnography of City Life. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(2), pp.677–685. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01151.x.

Dening, G. (1995). The death of William Gooch : a history’s anthropology : Dening, Greg : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive. [online] Internet Archive. Available at: https://archive.org/details/deathofwilliamgo0000deni [Accessed 7 Apr. 2025].

Escalante, A. (2024). ¡Que Ricky Renuncia!: Protest-as-Care and Saintly Devotion in Loíza, Puerto Rico. Transforming Anthropology, 32(2), pp.109–116. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/731718.

Gemmett, R.J. (1970). The Beckford Book Sale of 1808. The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 64(2), pp.127–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/pbsa.64.2.24301655.

Hartman, S. (1997). Scenes of Subjection. Oxford University Press.

Keeling, K. (2007). The Witch’s Flight. Duke University Press.

LeBrón, M. (2018). Puerto Rico’s War on Its Poor. [online] Boston Review. Available at: https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/marisol-lebron-puerto-rico-war-poor/.

Lee, E.S. (2014). Living Alterities: Phenomenology, Embodiment, and Race. [online] State University of New York Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.18253593.

Manuel, P. (1994). Puerto Rican Music and Cultural Identity: Creative Appropriation of Cuban Sources from Danza to Salsa. Ethnomusicology, 38(2), pp.249–280. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/851740.

McKittrick, K. (2013). Plantation Futures. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism, 17(3), pp.1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/07990537-2378892.

Rivera Diaz, M. (2024). Colorblind tools: global technologies of racial power. Latino Studies. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41276-024-00475-1.

Rivera, M. (2016). Pal mundo: El mundo académico ante el reggaetón de los noventas pa’ acá. Umbral.

Rivera-Rideau, P.R. (2015). Remixing Reggaetón. Duke University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11hphs8.

Rodríguez Centeno, M. (2021). ‘Pe-pe-perreito o ponerle el cuerpo (cuir) a lo político en Puerto Rico’. [online] Beatriz Llenín Figueroa, editora, Actas VIII Coloquio ¿Del otro lao? perspectivas y debates sobre lo cuir. Arte y activismo cuir en el Puerto Rico contemporáneo. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/66869217/_Pe_pe_perreito_o_ponerle_el_cuerpo_cuir_a_lo_pol%C3%ADtico_en_Puerto_Rico_ [Accessed 7 Apr. 2025].

Snorton, C.R. (2017). Black on Both Sides. doi:https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctt1pwt7dz.

Trouillot, M.-R. (2003). Anthropology and the Savage Slot: The Poetics and Politics of Otherness. Global Transformations, [online] pp.7–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-04144-9_2.

Woods, C.A. (1998). Development arrested : the cotton and blues empire of the Mississippi Delta. New York: Verso.

Young, I.M. (2005). On female body experience : ‘Throwing like a girl’ and other essays. Oxford University Press eBooks. Oxford University Press.