When there are no words left to say, we turn to the power of image to fill the gaps. Language can be twisted, left vulnerable to manipulation as the individual processes what is occurring. Photography becomes an honest means of communication, especially in the moments of humanity where the lines of what is right and wrong are blurred. It can be argued that the photographer becomes the one of moral high ground, the lens acting as if it were an eye that sees all. With the legacies of dictatorship leaving much disinformation and corruption in the timelines of information, it becomes hard to know what to believe. Hitting the Global South hardest, we can trace this through how it is rooted in Latin America – looking towards Chile as a prominent example. Despite the horrors that were perpetrated by Pinochet’s hellish regime, there is a plethora of politically charged art and culture which was generated as a result of it. With music from the likes of Victor Jara and Los Prisioneros, written words from Isabel Allende and Diana Arón, films such as Machuca, as well as photographers like Hernán Parada. What all these artists have in common is an understanding of the collective suffering experienced during and after the regime. Focusing on Hernán Parada’s photography, I will be investigating how image has been utilised as a tool of resistance against human rights abuses. In particular, I will be looking at how grief in public memory is essential to resistance.

September 11, 1973 is a bloody stain in the timeline of the country – the day that Chile’s government was taken over by the military. President Salvador Allende died during the assault on La Moneda Palace, and his death was followed by seventeen years of dictatorship under General Augusto Pinochet. During this period, thousands of citizens seemed to ‘disappear’. Loss and suffering was prominent in many families across the nation, leading to missing persons campaigns on an individual and mass scale. Naturally, photographs were at the forefront of these campaigns (so that strangers could identify the faces that they were looking for). Roland Barthes frames the photograph as being something which proves the existence of something and its reality; the person, the event, the place. As large numbers of people began to disappear, desperation to find their loved ones hit. Floundering between showing photographs from family collections and their state issued identity cards, anything was shown to get their faces out in the public. With the family photo album ripped apart, you’re forced to see those ‘arrested-disappeared’ as loved beings with connections to the world. Having played their role in social order as expected, their disappearance is made to seem more distantly than something deserved or consequential. As Nelly Richard explains it, there is an unnerving tension between the innocence captured in these traditional and ritualistic moments of life (weddings, baptisms, birthdays, picturesque family moments) and the dramatics of what these images actively represent in a moment of national tragedy – a victim. Pictures taken from ID cards further prove what Barthes says, if these state issued images exist then how could the very agents of that cause deny that these people ever existed? Here was evidence that these were individuals who had abbided to the state apparatus, a victim of a bureaucratic system which has ultimately left them exposed to state violence. With the erosion of time and memory, there is a haunting transformation of the ID; reducing these lost individuals to numbers, they are stripped of uniqueness and duplicated to create a ‘mass produced’ citizen. The more a human being is reduced to a number, the easier it is to forget their humanity – “the death of one man is a tragedy, a million is a statistic”.

“Quiero saber si me pueden dar alguna información de dónde estoy, porque en estos momentos estoy desaparecido” – Hernán Parada

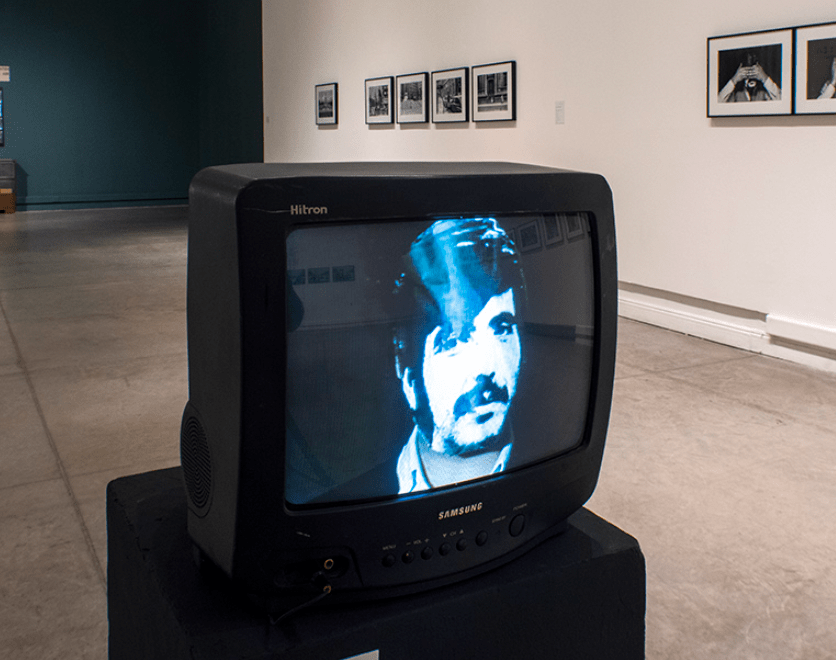

“I want to know if you can tell me where I am, because right now, I am missing” are the words spoken by Hernán Parada in his seminal ‘Obrabierta’ artworks. He speaks these words out onto the street, using this physical interaction to unite his artwork to the general public whilst recording it on camera. Through doing so, Parada replicates an experience of shared collaboration to bring ‘Obrabierta’ to life. Bodily performance and technology are combined to create a new series of events where his brother is able to fight for his own rights. The photographs that resulted from it consisted of him wearing a mask of his brother Alejandro Parada’s face, the same black and white photocopy blurring the line between him and his brother. Returning to the identity card image, Hernán claimed to have “fallen in love with his expression”. There is truth to what Hernán says, Alejandro is serious in a manner that is compliant to ID requirements yet there is a sense that his mouth is turned up in an almost smirk. Perhaps it is the illusion that is brought about as a viewer, knowing what we know and how little Alejandro does. Hernán takes it one step further, situating himself in different public spots around Santiago. Though his art is unique to his experience, many can feel familiar with his art before having seen it. With it being common to see people with the faces of missing persons pinned to their shirts, he takes it one step further by ‘sharing his body’. Hernán’s face is always enveloped by the mask. Rather than shrouding him in mystery, his brother’s face immediately exposes him as vulnerable. Doing the most intimate act possible, he shares his body with the person he loves most. It often feels that we, as human beings, exist as singular souls within a physical vessel, but ‘Obrabierta’ demonstrates that our existence is built off the relationships we have with others. To be stripped so violently from someone who shares your identity leaves more than just a hole in the world, it leaves an emptiness within yourself. By using his own body, it emphasises the physical loss of his brother’s body. There is visibly less mass in the world following what occurred, as his body was never found. Wearing a mask emphasises this fact of violence, enhancing the kidnapping and disappearance. Oddly enough, the act of wearing a mask allows him the privacy to mourn whilst also publicising it as an act of resistance. Hernán is not the face of his operations, Alejandro is. The mask blurs his identity to make him unknown whereas Alejandro is a familiar face. Not because we have met him, but because of the static photocopy that lets us see his features so clearly. Reach into your wallet and you will see the same face in the uniformity of your own state issued identity card. For those at the time, the artwork serves as a reminder to all the mothers who have frantically run around the city asking who had seen their loved one.

At the exit of the metro for the Central Station, we gaze into the crowd in an attempt to spot Parada. Stations exist as a constant flux of bodies; people coming and going from their places of work and study, waiting to see their friends get off the carriageways, and as a place to protest. This was true in the 70s and even truer now. Chile’s inequality hit a peak when metro’s shot up in prices, leading to protests in 2019 that were centered in the metro. Awasthi writes of the symbolism behind train stations being one of force, rupturing the social and economic fabric of nations by introducing class mobility. With the irony of violating this symbolism by making ticket prices inaccessible to the people who are buying them, we can view protest in this space as a method of restoring this balance. Jumping over a turnstile is more than just an act of defiance, it is a reclamation of freedom – a physical assertion of one’s right to occupy public space. Returning to Hernán’s photograph, there is no violence or chaos to be seen. Everyone is facing the camera with their faces uncovered, almost in solidarity with Alejandro. It becomes difficult to differentiate Alejandro from the other people, almost as if any of them could simply be mourners with masks on too. Whilst documentary photography often chooses to show the brutality of violence as a method of advocating for human rights, I think Hernán’s work highlights a different side of the struggle. Many Latin American countries have been overexposed to violence throughout the centuries, whether it is through its media or through public military displays that have left them exposed to collective trauma. When thinking about photography which motivates advocacy, documentary photography is a useful aid but not a vessel for thought. Using art without violence makes it easier to share the subtleties of individual suffering, instead of detaching the human because of a repeated and standardised violence. In Hernán’s work, there is no way to disregard or detach the personal experience from the photograph; his artwork “is an important way of countering a culture of silence”, by sharing a deeply upsetting story through a more digestible medium.

The vulnerability which he has to expose his mourning so openly is an act of defiance itself. Globally, state’s have stripped so many disadvantaged communities from the most basic human right and emotion of bereavement. To be able to mourn is a human right, to conduct the final ritual of the life cycle is a human right, to process the pain you’ve been caused is a human right. I find it necessary to reference the experiences of indigenous Mapuche people, who experienced the grief of a ‘disappeared person’ long before and after Pinochet. Mapuche’s murdered by the state describe these as ‘unfinished people’ [no-finados], whose spirits are trapped to certain physical spaces. Mapuche belief is that the past plays an ongoing role in the present and future, effervescent in the everyday. It is therefore that the Mapuche see state violence as a continuous fact in life, with the time passing intensifying an understanding of self in contrast to the state. Whilst Mapuche suffering is often excluded from collective mourning, we can apply their ideology to understand how Hernán’s agony translates to advocacy for human rights. Hernán sees that this state violence has trapped Alejandro to the last places he may have wandered – the train station, parks, the university campus. If we interpret Hernán’s artwork as a representation of an ‘unfinished person’, then he disrupts the Western narrative of time and memory so that the past can exist in the present. Similarly, the local Mapuche people believe that they are embodying the missing when they fall ill, relating this form of suffering to the traumas they directly experience from growing inequality. If we apply indigenous thinking to Hernán’s act, we can see how he processes the injustice in the world by becoming the spirit of his brother in the places where his body remains trapped. His brother is stood outside the station in the past, present, and future (as the image exists forever), reaching out to people who still have the capacity to generate change.

Hernán Parada’s use of the public space acted as a “mass exhibition in the public space”, however I wish to discuss Parada’s works as a display within institutions. His work was displayed in a solo exhibition at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (MAC) [Chile’s Museum of Contemporary Art] in 2022 as well as a group exhibition as the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende [Museum of Salvador Allende Solidarity], both with the addition of an archive he created for his brother. Containing unexhibited artworks as well as family albums of his brother and the activity that he engaged in alongside his visual protest. As a part of the group of Agrupación de Familiares de Detenidos Desaparecidos [Association of Relatives of the Detained-Disappeared], his engagement with politics went beyond what is originally seen. Beyond granting us deeper knowledge behind the intention of his work, photographic archives have more practical uses in the role of human rights activism. Archives play an important role in understanding the changing landscapes of the globalised world, as we cannot separate the act of archiving from the people in control of them. Much archival material that was inaccessible before has been made open access as narratives of the state shift. Whilst there are ‘official’ archives with specific processes, artist and photographer archives serve as a grassroots and decolonised approach to history. Archives have the capacity to shape collective memory, because unlike individual memory, it is created by the material objects which prop up the national imagination.

“all memory is individual, unreproducible – it dies with each

person. What is called collective memory is not a remem-

bering but a stipulating: that this is important, that this

is the story about how it happened, with the pictures that

lock the story in our minds. Ideologies create substantiating

archives of images, representative images, which encapsu-

late common ideas of significance and trigger predictable

thoughts, feelings”

UNESCO (setting the pace for culture and human rights advocacy) has supported projects with the National Library of Chile that focus on digitising the personal archives of artists, making the ‘counter archive’ a relevant narrative. I use the word ‘narrative’ because the photograph, the archive, the national imagination, are all simply stories from different perspectives. This is not a disadvantage when one is aware of it; rather it can make us insightful and empathetic humans that understand that there is not one way to interpret the world. If there is one final idea that can be gathered from Hernán Parada’s contribution to human rights activism is that his perspective is one but we must always go out and seek more. The suffering of one is the suffering of many, we all have individual narratives to share – and it can never hurt to listen to one more.

Photography has been used to advocate for human rights in Latin America through infiltrating the public space, corrupting memory and time, grieving state imposed violence communally, and through its continual relevance in museums and archives. The ‘unfinished people’ insinuate that there might be a way to help them end their journey. Hernán Parada shows us this by making sure that even though his brother’s body is gone, his face will be burned in the minds of so many. Alejandro’s footsteps never stopped running through Santiago, making him a powerful narrator even without a voice. Ultimately, Hernán was just a young student who longed to see his brother again; looking out at the crowds, he sees him every day.

Bibliography

Assmann, Aleida. 2008. “Transformations between History and Memory.” Social Research 75 (1): 49–72. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40972052?seq=1.

Awasthi, Aruna. 2011. “RAILWAYS and CULTURAL HISTORY: A STUDY of POETIC REPRESENTATIONS.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 72: 955–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/44146787.

Bacigalupo, Ana Mariella. 2016. Thunder Shaman. https://doi.org/10.7560/308806.

———. 2024. Shamans of the Foye Tree. University of Texas Press. https://utpress.utexas.edu/9780292782846/.

Barthes, Roland. 1966. Introduction to the Structural Analysis of the Narrative.

———. (1980) 2020. Camera Lucida. London: Vintage Classics.

Betancur Roldán, María Cristina. 2022. “Archival Traditions in Latin America.” Archival Science, May. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-022-09393-4.

Dillon, Lorna. 2024. “Participatory Needlework and Human Rights Activism.” Journal of Romance Studies 24 (1): 73–95. https://doi.org/10.3828/jrs.2024.6.

Farman, Jason. 2013. Mobile Interface Theory. Routledge.

Jean-Paul Sartre, and Elkaïm-SartreArlette. 2004. The Imaginary : A Phenomenological Psychology of the Imagination. London: Routledge.

Jelin, Elizabeth. 2010. “The Past in the Present: Memories of State Violence in Contemporary Latin America.” Palgrave Macmillan UK EBooks, January, 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230283367_4.

Latin, KCL. 2020. “KCL Latin American Society.” KCL Latin American Society. April 22, 2020. https://www.latamkcl.co.uk/elcortao/fake-news-in-latin-america-the-legacy-of-pinochet.

Longoni, Ana. 2010. “Photographs and Silhouettes: Visual Politics in the Human Rights Movement of Argentina.” Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry 25 (September): 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1086/657458.

Mariella Bacigalupo, Ana. 2018. “The Mapuche Undead Never Forget: Traumatic Memory and Cosmopolitics in Post-Pinochet Chile.” Anthropology and Humanism 43 (2): 228–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/anhu.12223.

Parada, Hernán. 2020. “Obrabierta.” Https://Hernanparada.cl/Exposicion-Obrabierta/. 2020.

Preda, Caterina. 2017. Art and Politics under Modern Dictatorships : A Comparison of Chile and Romania. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Richard, Nelly. 2018. Eruptions of Memory. John Wiley & Sons.

Scott, James C. 1990. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. JSTOR. Yale University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1np6zz.

Sontag, Susan. 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

UNESCO. 2025. “National Library of Chile: Preservation of Photographic, Audiovisual, and Sound Archives from the Dictatorship Era.” Unesco.org. 2025. https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/national-library-chile-preservation-photographic-audiovisual-and-sound-archives-dictatorship-era.

Vidal, Aldo . 2025. “Lista de Mapuche Muertos Post Dictadura En Relación al Llamado ‘Conflicto’ Mapuche.” Mapuche-Nation.org. 2025. https://www.mapuche-nation.org/espanol/html/documentos/doc-104.htm.